I will be moving these posts over to wordpress and incorporating into my lab webpage. The new link will be:

https://tattersalllab.com

Ramphastos Ramblings

A personal blog from a Canadian Comparative Physiologist. May include topics from Evolutionary Physiology to Conservation Physiology to basic animal physiology. Ramphastos is the genus name of the Toco Toucan, an animal that signifies everything I find fascinating about animal evolution.

Thursday 24 March 2016

Tuesday 1 March 2016

Thermal Camera Showdown - FLIR ONE vs. FLIR SC660

Last summer, I had a high school volunteer (Padraic Odesse) join my lab for a few hours a week to help out my graduate students with data analysis. To assist him with learning about imaging, technology, and experimental design, I set up a simple experiment for him to test. Since I am often asked by people whether the new consumer oriented thermal imaging products are 'up to snuff' or useful as research devices, I gave my lab assistant the task of capturing images with a high end thermal camera (FLIR model SC660, which has 640x480 image resolution and thermal resolution ~0.03C) and with the $300 dollar iPhone attachment (FLIR ONE, image resolution 80x60, enhanced up to 160x120, not sure its technical specs on temperature detection).

Here is what the FLIR ONE looks like, nestled next to my lab standard for temperature measurement (accuracy ~0.2C), a thermocouple meter from Sable Systems International :

Here is the competition, my FLIR SC660 (it has a built in tuning function):

Here is our constant temperature source, a circulating water bath with precision temperature control:

Which is easy to confirm temperature with the thermocouple meter:

Since distilled water has a high and known emissivity, it makes it an easy target to produce thermal images from that will be consistent over time (plus/minus error and resolution of the controller).

Here is a sample image taken with the FLIR SC 660:

Here is a sample image taken with the consumer product, FLIR ONE:

As I describe elsewhere (I will post a link to a review paper that will be in press in a month or so), the FLIR ONE product saves its default image as a composite of a thermal image with a haloed/outline image in the usual FLIR JPG format. So, if you have other FLIR software, you can extract the actual thermal image and do proper thermography on the image. If you don't have their software, then you are basically stuck with whatever the spot sensor tells you what the temperature is. I would not trust the spot temperature measurements. The software does not allow you to set the emissivity precisely or numerically, and distance and other parameters are not available. Use the spot temperatures cautiously!

Here is what the FLIR ONE looks like, nestled next to my lab standard for temperature measurement (accuracy ~0.2C), a thermocouple meter from Sable Systems International :

The camera is a nifty attachment to my iPhone 5, although I look like I'm carrying a bulky phone around with me. The attachment is actually two cameras in one. The one lens is the lens that allows long wavelength infrared radiation to pass through to the detector and the other lens is probably very similar to an iPhone camera. Because they are adjacent to each other, they very nearly capture a similar field of view. The FLIR software lets you do neat things with overlaying the images, but to be honest, I find the whole outline overlay to be annoying. Great fun for non-professionals, but annoying if you wanted to use this camera for scientific purposes.

The FLIR ONE has a little pull down switch that turns the device on, but also acts as a shutter control. I'm not 100% certain what FLIR does, but given how their other cameras work, what is likely is that the when the shutter is pulled down, the thermal sensor is receiving a constant signal that it uses to "calibrate" itself. FLIR calls this "tuning", not "calibrate" and I am putting things in quotes since I don't quite know. What other thermal imagers tend to do is use a shutter like this as a reference signal, and also for Non-Uniformity Correction of the pixel array. If the reference signal is at a known and constant temperature, you can, in essence, calibrate the thermal detector to a more stable source. It's clearly more complicated than that, but suffice to say, the FLIR ONE demands to be tuned on a regular basis!

Mounted on a tripod ~0.4m from our temperature source:

Here is our constant temperature source, a circulating water bath with precision temperature control:

Which is easy to confirm temperature with the thermocouple meter:

Since distilled water has a high and known emissivity, it makes it an easy target to produce thermal images from that will be consistent over time (plus/minus error and resolution of the controller).

Here is a sample image taken with the FLIR SC 660:

Here is a sample image taken with the consumer product, FLIR ONE:

As I describe elsewhere (I will post a link to a review paper that will be in press in a month or so), the FLIR ONE product saves its default image as a composite of a thermal image with a haloed/outline image in the usual FLIR JPG format. So, if you have other FLIR software, you can extract the actual thermal image and do proper thermography on the image. If you don't have their software, then you are basically stuck with whatever the spot sensor tells you what the temperature is. I would not trust the spot temperature measurements. The software does not allow you to set the emissivity precisely or numerically, and distance and other parameters are not available. Use the spot temperatures cautiously!

Error Analysis

So, my lab assistant diligently captured an image with the two cameras, taken at the same distance and at 8 different water temperatures (5 to 40C). We now had two camera's data capturing the same source under identical conditions, and so we analyzed the water temperatures using FLIR Thermacam Rearcher Pro, setting object distance to 0.4 m, emissivity to 0.98 (http://www.infrared-thermography.com/material-1.htm), and reflected and atmospheric temperatures to 20C (which was the room temperature.

So, here are the results:

At a quick glance, they both perform quite well. Look at those R2 values! Rarely see that in biology. But these are engineered devices. See how the FLIR ONE deviates in temperature at the low and high temperatures. This tells me that there is some atmospheric contamination or attenuation of the signal the camera picks up. The reason things look really accurate near room temperature is because the formula for calculating temperature predicts that if all temperatures are similar to each other, the contaminating radiation signal will be similar to the object signal.

If you narrow in on how large the error is this will make a bit more sense. Take the difference in Camera - Actual temperature for all 8 measurements. The mean absolute error will tell you whether the camera is reading higher or lower than actual temperature (absolute value simple removes the negative sign). The standard deviation of those measurements is a metric for the resolution/sensitivity of the measurements.

Mean absolute error for the FLIR SC 660: 0.128°C

SD of the error for the FLIR SC 660: 0.0873°C

SD of the error for the FLIR SC 660: 0.0873°C

Mean error for the FLIR ONE: 0.603°C

SD of the error for the FLIR ONE: 0.41°C

On the whole, both cameras perform rather well under these optimized conditions, although clearly the SC 660 performs better. An error of ~0.128°C is quite low, whereas the FLIR One error is ~5 times higher at 0.603°C. This kind of error may be related to the electronics, warm-up time, or the sensitivity of the sensor itself, to name a few.

So, for measuring purposes, the FLIR ONE isn't too bad. Certainly not as inaccurate as I had feared it might be (except see below). But, remember, we were performing the analysis using thermography software that allows for some correction of environmental variables, and we were constantly tuning the FLIR ONE. Depending on your measurement purposes, you might be ok, but the best error you will get under optimal conditions appears to be greater 0.6°C.

Confounding Issues with the FLIR ONE

Because we ran the error analysis above under ideal conditions, we wanted to be a little more realistic with the FLIR ONE since it is likely to be used by scientists as an affordable alternative to work in the field.

The possible confounding issue I am referring to is the warm-up time and the camera's physical temperature itself. As is usual with cell phones, people are likely to keep the device in their pocket, or maybe leave it exposed to the elements. If you then turn the thermal camera on and take a spot measurement, there is bound to be error associated with the lack of tuning, but also because the camera temperature is changing while you are making the measurements, which would confound the tuning process itself.

So we took as realistic an approach as possible ran the measurements 3 different ways. We stored the FLIR ONE in a cold room (5°C), a warm room (40°C) and at room temperature (20°C) for 30 minutes prior to use at room temperature. Then, we turned the thermal camera on and rapidly started recording the spot temperature estimates every 10 seconds, tuning the camera whenever it demanded (there is a tilde ~ symbol that tells you when to tune). Here are the resulting data (apparently we only ran the cold transfer for ~180 seconds, but the data are still obvious:

If you keep the camera in a cold room, it will severely underestimate temperature (by an average of 5.9°C!!). It does not return to normal temperatures within 180 seconds.

If you keep the camera in a warm room, it will overestimate temperature (by an average of 1.0°C). Strangely it does not seem to converge toward the real temperature within our 10 minute long experiment. Note in the error analysis measurements before, the FLIR ONE did pretty well at measuring objects ~20°C, so this overestimate is due to persistent temperature effects on the device itself.

Finally, the rapid on data show you how the FLIR ONE really performs from rapid turn on (without a thermal equilibration problem), through various cycles of tuning. Each time it jumps in temperature corresponds to when we tuned it. It eventually converges toward the real temperature after ~8 minutes.

Its overall error is ~0.89°C during this warm-up period.

So, can you use the FLIR ONE for real science? Lot's of ifs and buts, and if you are prepared to calibrate it and check it, go for it (with the caveats above about a 5 times level of error). I like mine for teaching purposes since it is portable and fast to use, but I will still use my SC 660 for most of my research purposes, due to the versatility of video capture functions, image resolution, and electronic stability. If you choose to publish a scientific paper with a FLIR ONE, don't ask me to be the reviewer. I would insist on a calibration curve and assurance that these parameters have all been assessed.

Fine Print

I am not affiliated with FLIR, nor do I receive revenue, salary, or funding from them, so this post should not be interpreted as an endorsement. Over the years, I have sent them a lot of business from researchers who ask my advice on thermal imaging products, but I can safely claim that I have received no freebies, hand-outs, or in-kind contributions from FLIR. Of course, I would be most grateful if FLIR did give me a free thermal camera or a news lens for all the fine press I give them! If anyone from FLIR is reading this, please take note: you're a big company and perhaps you might want to support basic research.

Tuesday 26 January 2016

Why Scientific Discovery is Important & Why Science is Supposed to be Fun

It has been a while since I blogged, and I could go into details about a desire to 'disconnect from the online world' or give excuses that 'there are too many things that occupy my time', both of which are true...but that is for another time.

I wanted to post some reflections following the publication of a paper that represented contributions from a number of brilliant collaborators, particularly because we need a good news story in basic sciences. I also wanted to reflect a little to give younger scientist reason to be positive about science.

Last week, we (collaborators from Brasil and Canada) published a basic discovery paper entitled: Seasonal reproductive endothermy in the tegu lizard" in Science Advances, the open access sister journal to Science, published by the AAAS.

The discovery has been well covered in the media already (see links here), and I will not go into too many details here, since it is all openly available at the link above, except to say that we discovered an animal that is usually considered to be ectothermic ("cold-blooded" is the horribly inaccurate term used by non-scientists) can become endothermic ("warm-blooded" - another equally uninformative and antiquated term to describe a complex array of metabolic changes), and it does so during the reproductive season. As careful scientists, we did not comment in the study on their reproductive activities or indeed we had no measurements of what they were doing, so the link to reproduction is indirect at the moment. The study was simply an observation that they become warmer during this time of the year and that the degree to which they warm up cannot only be explained by the usual suspects (e.g. behavioural thermoregulation, thermal inertia).

Here are the results of the study, depicted simply as a thermal image:

Shown above is a small group of tegu lizards sharing the same burrow (they do so voluntarily, although probably with a little "aggro"). This image was captured in the early morning hours (~5-6am) before sunrise during the breeding season, so the tegus should have been as cold as they could be from the previous day of basking. One is a little bit cooler than the other two in temperature, but all three are quite a bit warmer than their surroundings. They are achieving this through a rise in metabolism and because of an escape from the outside air, are able to slow their rates of heat loss.

Indeed, occasionally, a tegu doesn't make it back into the burrow at night, so that the next morning when we find it, it is quite frigid. This is because the endothermy isn't operating at the same capacity of that of a bird or mammal and that it is not necessarily thermoregulatory in nature. Here is a rather cool tegu found trapped outside a burrow on a cool night (~6am), with a low body temperature:

Anyhow, what is more important for me to write about is something I only thought about after the media started calling us, and that is that not all science follows the painfully boring description kids are given in school about the laborious scientific method. Allow me to explain by way of giving the "human side" to a fun research collaboration, while also writing this as a parable for the way that science truly proceeds.

Fast forwarding to when Colin returned to Canada, he now had a massive amount of data on the daily changes in heart rate, breathing rates and body temperatures in a cohort of tegu lizards and still had to make sense of that. In many ways, this project was a highly sophisticated Natural History project. We were initially interested in knowing whether tegus went into their burrows and reduced metabolism in the winter and needed to do this under natural conditions, which is where our Brasilian colleagues came in.

My advice to junior scientists? Don't give up, but be prepared to think clearly and seek your motivation to do science (i.e. discovery research) from your own inner enthusiastic and curious kid, rather than your colleagues or your mentors!

This research was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada</a> (to W.K.M. and G.J.T.), FAPESP, and CNPq through the INCT in Comparative Physiology</a> (proceeding nos. 2008/57712-4 and 573921/2008-3). D.V.A. was supported by research grants from the FAPESP (proceeding nos. 2010/05473-6 and 2013/04190-9) and CNPq.

I wanted to post some reflections following the publication of a paper that represented contributions from a number of brilliant collaborators, particularly because we need a good news story in basic sciences. I also wanted to reflect a little to give younger scientist reason to be positive about science.

Last week, we (collaborators from Brasil and Canada) published a basic discovery paper entitled: Seasonal reproductive endothermy in the tegu lizard" in Science Advances, the open access sister journal to Science, published by the AAAS.

The discovery has been well covered in the media already (see links here), and I will not go into too many details here, since it is all openly available at the link above, except to say that we discovered an animal that is usually considered to be ectothermic ("cold-blooded" is the horribly inaccurate term used by non-scientists) can become endothermic ("warm-blooded" - another equally uninformative and antiquated term to describe a complex array of metabolic changes), and it does so during the reproductive season. As careful scientists, we did not comment in the study on their reproductive activities or indeed we had no measurements of what they were doing, so the link to reproduction is indirect at the moment. The study was simply an observation that they become warmer during this time of the year and that the degree to which they warm up cannot only be explained by the usual suspects (e.g. behavioural thermoregulation, thermal inertia).

Here are the results of the study, depicted simply as a thermal image:

Shown above is a small group of tegu lizards sharing the same burrow (they do so voluntarily, although probably with a little "aggro"). This image was captured in the early morning hours (~5-6am) before sunrise during the breeding season, so the tegus should have been as cold as they could be from the previous day of basking. One is a little bit cooler than the other two in temperature, but all three are quite a bit warmer than their surroundings. They are achieving this through a rise in metabolism and because of an escape from the outside air, are able to slow their rates of heat loss.

Indeed, occasionally, a tegu doesn't make it back into the burrow at night, so that the next morning when we find it, it is quite frigid. This is because the endothermy isn't operating at the same capacity of that of a bird or mammal and that it is not necessarily thermoregulatory in nature. Here is a rather cool tegu found trapped outside a burrow on a cool night (~6am), with a low body temperature:

Anyhow, what is more important for me to write about is something I only thought about after the media started calling us, and that is that not all science follows the painfully boring description kids are given in school about the laborious scientific method. Allow me to explain by way of giving the "human side" to a fun research collaboration, while also writing this as a parable for the way that science truly proceeds.

The Best Laid Plans of Lizards and Men Often go Awry

This study began as a 2 year long MSc project for Colin Sanders, who was working with Dr. William Milsom at the University of British Columbia (where I did my post-doc). Colin, Bill and myself went down to Brasil in 2003/2004 to initiate a project examining the year-long changes in heart rate, breathing rate and body temperature in tegu lizards in a semi-natural environment. The initial basis for the study was to examine a lizard that would hibernate (i.e. go dormant) at relatively warm temperatures. Our Brasilian colleagues (Abe and Andrade) had laboratory data suggesting that tegus would go dormant in the winter. We had valid physiological reasons for why this was a interesting question (not initially about endothermy) and that was Colin's MSc project. How did we do this? We implanted little electronic devices that would measure an EKG and EMG and body temperature continuously and save this data to a computer. The entire project was instrument heavy and indeed, our equipment was tied up in Brazilian customs for 6 weeks, nearly preventing the launching of his research! I wrote a Matlab script to analyse the massive amount of raw data we were collecting from the radio-transmitting telemeters. Colin had to endure months of staring at the computer screen to verify the script was working properly. All totalled, we collected Gigabytes of data to computers that had no DVD drives and no network access. Suffice it to say, Colin had a lot of sleepless nights and frustrations of running my rather unsophisticated computer code. Skype and email were our friends, but it made discovery a distant and future goal.Fast forwarding to when Colin returned to Canada, he now had a massive amount of data on the daily changes in heart rate, breathing rates and body temperatures in a cohort of tegu lizards and still had to make sense of that. In many ways, this project was a highly sophisticated Natural History project. We were initially interested in knowing whether tegus went into their burrows and reduced metabolism in the winter and needed to do this under natural conditions, which is where our Brasilian colleagues came in.

Collaboration and Camaraderie

We were able to pursue this research because of the friendly and collaborative nature of two key individuals, Dr. Augusto Abe and Dr. Denis Andrade. Since 2002, they have hosted myself in their lab (and homes!) for up to 1 or 2 months, almost on a yearly basis. They both have interesting research programs into South American evolutionary physiology and comparative biology and are incredibly knowledgeable about the natural history of reptiles and amphibians of Brasil. They had both studied tegu hibernation in the lab as well. Not only was their lab designed to allow us to study tegus in their (almost) natural habitat, but visiting their labs is always a fruitful journey of discovery. My hats off to Augusto for having the foresight to build a world class facility to encourage and foster collaborations in our discipline, and my deep appreciation to Denis for being the on-site "supervisor" of the research in Brasil. It is not easy to remotely manage collaborations.Check, Refine, Eliminate other Explanations

Following our initial, but unplanned-for observations of lizards warming up in the reproductive season, we spent a few years (yes, this was a slow cooker project) discussing the possible explanations and trying to devise ways to convince ourselves that the heat was due to metabolic heat production. Colin's heart rate data did provide the best evidence of this, but we already recognized that reviewers would be inherently skeptical, since we were ourselves. At this stage, Dr. Cleo Leite and my student Viviana Cadena were invited to carry the torch and help provide the evidence that the tegus were not only capturing heat from the sun very efficiently and storing it. Bill and myself had a lot of friendly arguments about this, but Bill convinced us all that the initial observations were real and important. As a side project to his other research, Cleo collected three years worth of data on tegus during the reproductive period and transferring them back and forth from outside burrows to inside the lab where we had better control over ambient temperature, and along with Viviana's thermal images, we were able to show that tegus were still showing rather impressive amount of endothermy (2 to 3 degrees above ambient temperature) when placed in the lab for a week without access to insulating burrows, or nest material.Science is an Ongoing Learning Exercise

Along with wise and thoughtful contributions from all my co-authors, I was tasked with the unenviable job (hey, this is my story, so I can tell it this way) of writing the data up for publication. All of us suffer from procrastination when it comes to writing. Scientific writing is not simply formulaic, although there are clear and simple ways to present science accurately, I also think the best scientific papers also tell a story. So, I drafted the first version of the manuscript and knew we had a really cool observation but had to do my homework since we would need to place the work into the appropriate theoretical context. The evolution of endothermy has a long history of big thinkers testing hypotheses for how the ancestral condition of ectothermy could have overcome the energetic costs inherent to endothermy. How were we to put our years of observations into this context? Anyhow, I think we were all pushed a little outside our comfort zone.Don't Be Dismayed by Rejection

Once you think you have a potentially impactful paper, you do want it to be published somewhere where it will be read! It also is true (almost a cliche) that many scientists will aim for the top journals, only to receive that dreaded auto-email reply from Nature claiming that "...your manuscript is of insufficient immediate interest to our broader readership to justify its publication in Nature." That is fine. Push on and don't let that manuscript stagnate on your computer. So, that is what we did. We endured our rejection, made headways with a subsequent submission and actually were pleased with the chance to have a widely publicised paper that was also available in an open access venue.Take Home Message

Although the media attention surrounding discoveries are usually nice, they very often exaggerate the story and forget to comment on the importance of the team as well as the important role of accidental discovery. Serendipity should be more valued in science. It rarely is, and I worry that we train our students to become hypercritical hypothesis-driven automatons. Although I still think that science should be hypothesis-driven (you still need to know what you hope to achieve and be able to communicate this effectively when writing a research grant or defending your idea to a graduate committee), you also need the freedom to "follow your nose" if you come across a novel observation. Why can't we have both? Why can't we train people to think scientifically, accurately and carefully, while recognizing the value of thinking outside dogmatic constraints. Yet, granting agencies demand outcomes and outputs and governments like to link research to applications (read: commercial applications and jobs). Where is the joy in this approach? How does basic research fit into this?My advice to junior scientists? Don't give up, but be prepared to think clearly and seek your motivation to do science (i.e. discovery research) from your own inner enthusiastic and curious kid, rather than your colleagues or your mentors!

Funding Agencies Deserve their Credit

There are some funding agencies that do value basic research, and my hats off to them!This research was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada</a> (to W.K.M. and G.J.T.), FAPESP, and CNPq through the INCT in Comparative Physiology</a> (proceeding nos. 2008/57712-4 and 573921/2008-3). D.V.A. was supported by research grants from the FAPESP (proceeding nos. 2010/05473-6 and 2013/04190-9) and CNPq.

Tuesday 1 July 2014

Galapagos 2.0

Ramping up for the second field season in Galapagos, so I might start blogging a little more. It has taken a year to secure the permits and permission to conduct our research, so let's hope the data are interesting! I will eventually post about the data, but perhaps not until the paper(s) is/are published.

Fly out tomorrow morning....arrive in Galapagos on Thursday morning. Let's hope that all my equipment arrives safely.

Stay tuned...

Sunday 18 May 2014

BLISS-ful Spring

I'm taking a break from the usual blog entries to highlight a field-based research project that has been years in the making, but somehow part of my research interests.

Another research hat that I wear is one related to a population monitoring project in Algonquin Park. It seems appropriate this year, given the long cold winter and late spring, to chronicle the history of this project now, given the length of the study and the hope for the future.

It all starts with a small lake in Algonquin Park - Bat Lake.

Bat Lake is a small lake in Algonquin Park, located just north of Highway 60.

This lake is an unusual lake in that it is highly acidic (pH 4.3), fishless, rain/snow melt fed but permanent. This creates a unique combination for amphibians, since the lack of fish opens up opportunities for larval amphibians to survive and reproduce in abundance: nearly all of Algonquin Park's amphibians breed in it every year, making it a microcosm of the amphibians.

Here is a picture of Bat Lake:

To call it a Lake is actually a bit of a misnomer. Technically, it is a spruce bog, whose chemistry and biology has likely remained reasonably static since it formed following the retreat of the most recent glaciers ~10,000 years ago. Core sample data going back for the past 200 years suggests it has been fishless for at least that long, indicating that the acidity is not due to industrialization but is due to the unique features of the bog and the underlying bedrock which bestows very little buffering capacity to the water. Of the amphibians that breed in Bat Lake, the one this 'lake' is best known for is the Spotted Salamander, Ambystoma maculatum. Every spring, thousands of salamanders embark on a migration (probably ~1-2 km) to this breeding site.

History of the Bat Lake Inventory of Spotted Salamanders. (BLISS) The salamanders of Bat Lake have long been of interest to people familiar with Algonquin Park.

Pre 1990s - Numerous Algonquin Park Naturalists have helped to highlight the unique ecosystem at Bat Lake. It only takes a brief read of the Bat Lake Trail Guide to see the importance of salamanders to the surrounding ecosystem, where they are estimated to make up a large portion of the animal biomass.

1993 - I was first introduced to Bat Lake as an undergraduate student conducting a research project in the lab of Dr. Jim Bogart at the University of Guelph. I was not the best of research assistants and not much came of my work that summer (I am grateful to Jim for for his patience), but this little lake had a large influence on my thinking as a biologist.

1994 - 2006: Through the initiatives of Ron Brooks and the MNR, Bat Lake was included among other lakes in Algonquin Park for egg mass counts.

2004 - 2007: My lab began a series of studies on the symbiosis between the embryonic salamander and a algae that grows within the egg capsule. See here and here.

2008: My lab started formal Spotted Salamander monitoring at Bat Lake, referring to the project as BLISS. Aptly named, it turns out, since the students who tend to gravitate toward the project find working at Bat Lake a blissful experience! At least if they like working with herps.

2008 - 2012: The initial years of BLISS have worked out the 'bugs' of starting a field project in a remote part of Ontario far from where we all live. Various students have taken part over the years, including David LeGros, Patrick Moldowan, and Sean Boyle, all of whom I am proud to note have gone onto bigger and better things. Let's hope they become the next generation's biologists!

Present day: BLISS is currently co-managed by Algonquin Park Biologist, Jennifer Hoare, operationally run by Patrick Moldowan, with data deposited and analyzed by me (Glenn Tattersall). I feel sad that I am not more involved, but I have yet to manage to clone myself to allow me to get into the field in the springtime. Back in my lab at Brock, May is usually one of the busiest times of year as new students are starting research projects, and conference season is in full swing. Maybe one year I will actually get to experience the BLISS that is working in the field catching salamanders.

Into the future: The plan is for BLISS to remain a cooperative venture between the Ministry of Natural Resources/Ontario Parks, Universities, passionate biologists, and supported by volunteers! Check out this blog from Ontario parks showing their support for our project, as well as a creative writing impression (written by Patrick Moldowan) of what it is like to be a herpetologist anticipating the most exciting time of year: Spring!!

I hope to begin to write up some interesting results from BLISS in the next year or two, and will be happy to discuss questions with interested colleagues. So far, we are obtaining informative trends and associations between egg mass abundance and adult body size and changes in previous year's climate. The trick with a long-term dataset is how long to wait before publishing the results!

Of course, BLISS would not be possible without the Algonquin Wildlife Research Station and all the researchers who have made this place what it is. Check out their website for more information, but in short, this research station is primarily operated by dedicated university researchers who pursue research into Wildlife in the boreal forests of Ontario. Many Ontario university undergraduates have sunk their teeth into research at this station and fallen in love with science and the outdoors. Since federal funding for basic sciences is under threat, all field stations need support from the public, so please consider donating.

Happy Spring Everyone!

To call it a Lake is actually a bit of a misnomer. Technically, it is a spruce bog, whose chemistry and biology has likely remained reasonably static since it formed following the retreat of the most recent glaciers ~10,000 years ago. Core sample data going back for the past 200 years suggests it has been fishless for at least that long, indicating that the acidity is not due to industrialization but is due to the unique features of the bog and the underlying bedrock which bestows very little buffering capacity to the water. Of the amphibians that breed in Bat Lake, the one this 'lake' is best known for is the Spotted Salamander, Ambystoma maculatum. Every spring, thousands of salamanders embark on a migration (probably ~1-2 km) to this breeding site.

History of the Bat Lake Inventory of Spotted Salamanders. (BLISS) The salamanders of Bat Lake have long been of interest to people familiar with Algonquin Park.

Pre 1990s - Numerous Algonquin Park Naturalists have helped to highlight the unique ecosystem at Bat Lake. It only takes a brief read of the Bat Lake Trail Guide to see the importance of salamanders to the surrounding ecosystem, where they are estimated to make up a large portion of the animal biomass.

1993 - I was first introduced to Bat Lake as an undergraduate student conducting a research project in the lab of Dr. Jim Bogart at the University of Guelph. I was not the best of research assistants and not much came of my work that summer (I am grateful to Jim for for his patience), but this little lake had a large influence on my thinking as a biologist.

1994 - 2006: Through the initiatives of Ron Brooks and the MNR, Bat Lake was included among other lakes in Algonquin Park for egg mass counts.

2004 - 2007: My lab began a series of studies on the symbiosis between the embryonic salamander and a algae that grows within the egg capsule. See here and here.

2008: My lab started formal Spotted Salamander monitoring at Bat Lake, referring to the project as BLISS. Aptly named, it turns out, since the students who tend to gravitate toward the project find working at Bat Lake a blissful experience! At least if they like working with herps.

2008 - 2012: The initial years of BLISS have worked out the 'bugs' of starting a field project in a remote part of Ontario far from where we all live. Various students have taken part over the years, including David LeGros, Patrick Moldowan, and Sean Boyle, all of whom I am proud to note have gone onto bigger and better things. Let's hope they become the next generation's biologists!

Present day: BLISS is currently co-managed by Algonquin Park Biologist, Jennifer Hoare, operationally run by Patrick Moldowan, with data deposited and analyzed by me (Glenn Tattersall). I feel sad that I am not more involved, but I have yet to manage to clone myself to allow me to get into the field in the springtime. Back in my lab at Brock, May is usually one of the busiest times of year as new students are starting research projects, and conference season is in full swing. Maybe one year I will actually get to experience the BLISS that is working in the field catching salamanders.

Into the future: The plan is for BLISS to remain a cooperative venture between the Ministry of Natural Resources/Ontario Parks, Universities, passionate biologists, and supported by volunteers! Check out this blog from Ontario parks showing their support for our project, as well as a creative writing impression (written by Patrick Moldowan) of what it is like to be a herpetologist anticipating the most exciting time of year: Spring!!

I hope to begin to write up some interesting results from BLISS in the next year or two, and will be happy to discuss questions with interested colleagues. So far, we are obtaining informative trends and associations between egg mass abundance and adult body size and changes in previous year's climate. The trick with a long-term dataset is how long to wait before publishing the results!

Of course, BLISS would not be possible without the Algonquin Wildlife Research Station and all the researchers who have made this place what it is. Check out their website for more information, but in short, this research station is primarily operated by dedicated university researchers who pursue research into Wildlife in the boreal forests of Ontario. Many Ontario university undergraduates have sunk their teeth into research at this station and fallen in love with science and the outdoors. Since federal funding for basic sciences is under threat, all field stations need support from the public, so please consider donating.

Happy Spring Everyone!

Thursday 13 March 2014

Choosing the appropriate colour palette for thermal imaging in animals

This might sound like a strange thing to write about, the choosing of a colour palette for a thermal image. Why be concerned about which colour to use? Isn't it just for presentation? It happens to be one of my pet peeves with thermal imaging and how people new to the field do not appreciate how a colour choice might enhance small differences in temperature and overemphasize something rather minor.

My reasons will be illuminated below, but suffice it to say it relates ultimately to contrast and detectability of different temperatures through the use of colour itself.

From a computational perspective these concerns are not important. Almost all thermal imaging devices actually provide a proper temperature estimate for each pixel on the screen and as the images are typically stored in proprietary format in 12 or 14 bit files, this is not a concern from a quantitative perspective.

However, images captured are eventually converted into a digital format that is easily visualized by others, typically a jpg, png, tiff or bmp file. When presented online, then, you have a colourised rendition of temperature that is essence a filter of the real data mapped onto a pre-existing spectrum. This spectrum of colours is referred to as a palette in most graphical software.

There are a number of palettes that you might find available on your thermal imaging camera:

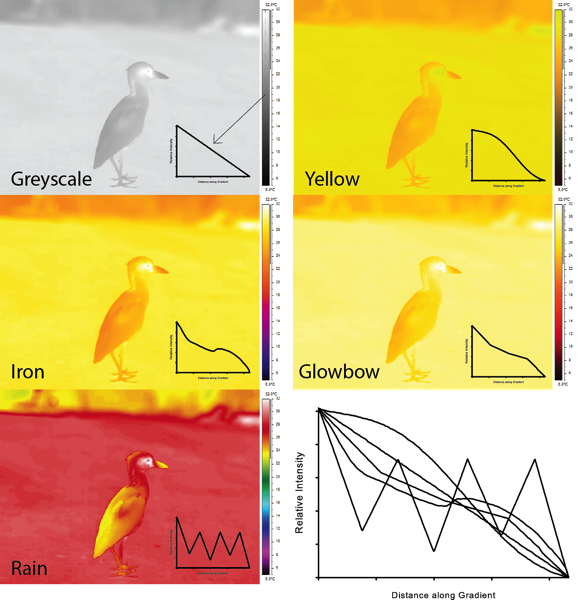

From left to right, these palettes are described as: Greyscale, Iron, Rain, Glowbow and Yellow (terminology comes from FLIR™). Each palette 'translates' temperature into a specific colour, with cold colours at the bottom (typically darker colours) and warm colours at the top (typically lighter colours).

At first glance it might be tempting to choose the funkiest colours, since it looks 'pretty' (this is a common reaction I get from people when I show them thermal images). Indeed, for some purposes this is entirely appropriate. Some palettes were designed specifically to create a large contrast in colour intensity across a narrow range of temperatures.

People generally do not believe me until i demonstrate it, but I often prefer to use the greyscale palette when imaging animals in the field for the simple reason that it is easier to focus on edges. Although greyscale might not offer a large degree of contrast between similar temperatures, it is a simple, natural scale of intensity where black is the lowest intensity, white is the highest intensity and greys provide a gradient of intensities in between.

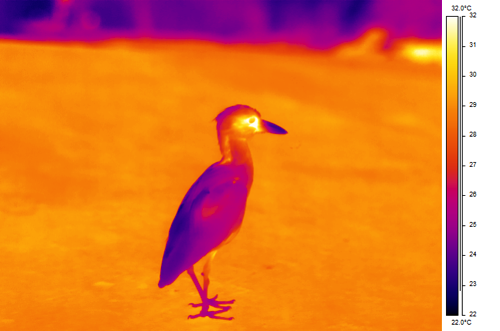

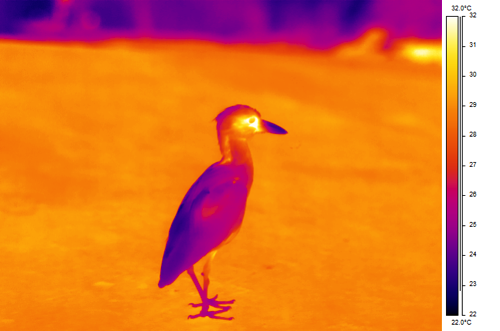

For presentation purposes and for publication purposes, however, a visually appealing colour might be appropriate (instead of greyscale). My own favourite palette is the Iron palette, as demonstrated in the following image of Yellow Crowned Night Heron from Galapagos:

Note how I have set the temperature range to go from 22 to 32C, where 22 is the lowest colour on the gradient and 32 is the highest. This maximizes the potential contrast of temperatures within the visible colour palette without saturating or eliminating any potential temperature.

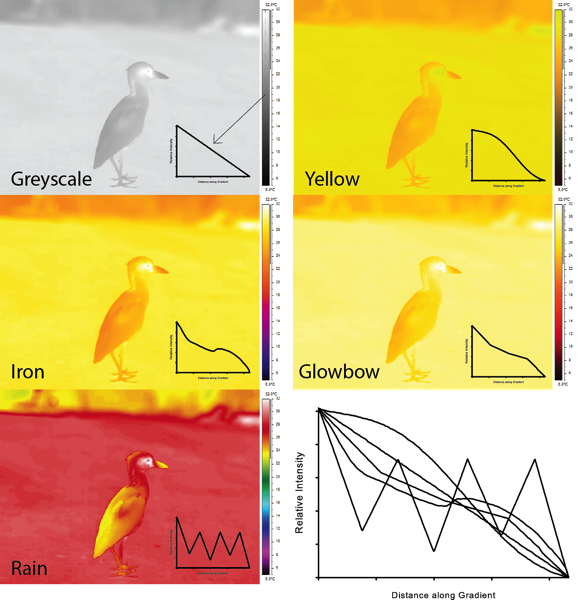

So, why all the fuss about palette choice? Let's consider the same image as I've shown you above, but this time using 5 different palettes. I have purposely rescaled the image to range from 5 to 32C, which actually masks some of the potential colour differences but it also shows how the different palettes may obscure potential temperature differences.

The picture above shows the yellow crowned night heron depicted using 5 different palettes. Inset line graphs depict the "intensity" of the gradient scale used in common units. All I did was import the images into ImageJ and drew a line down the gradient to obtain the "grey intensity" as a function of the colour palette. All palettes are compared in the lower right-hand graph to show how these different palettes translate "intensity" differently.

Although the human eye can certainly detect chromatic signals (i.e. different colours), the achromatic signals are what I am trying to highlight above. See how the different palettes show varying degrees of linearity and non-linearity. Clearly the greyscale gradient shows a monotonic decline in intensity, as you would expect for an achromatic response.

The other palettes however are not all the same as the greyscale. Sadly, my own favourite palette is shows a slightly curvilinear function with some intensities rising before falling again. The palette that comes closest to a greyscale, slightly monotonic decreasing palette is FLIR's Yellow palette.

Note how weird the Rain palette looks. The intensity rises and falls along the gradient itself. What this means is that your eye may be drawn to changes in achromatic signals in the colour palette and mistakenly consider them to be an incorrect temperature change. The Rain palette is an example of one of those favoured by people who initially play with thermal cameras. The images look striking, but my pet peeve about it is that it creates unnatural contrasts in colours that do not correspond to the actual temperature gradient. It also does not help that the beak and the back feathers look 'warm' because I am accustomed to yellow colours being warmer than red colours.

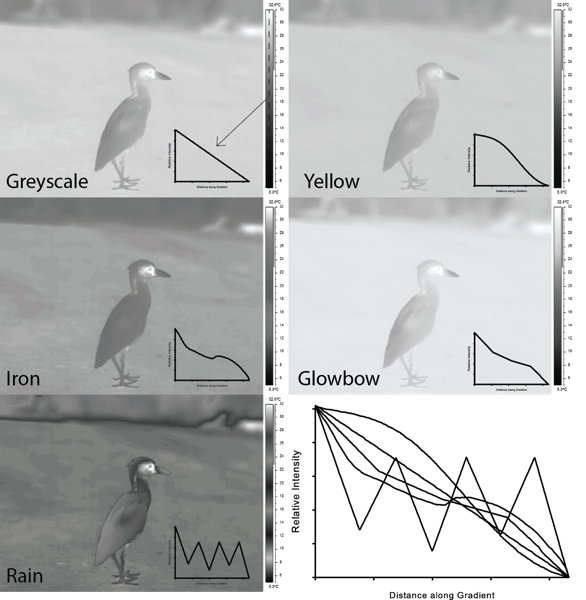

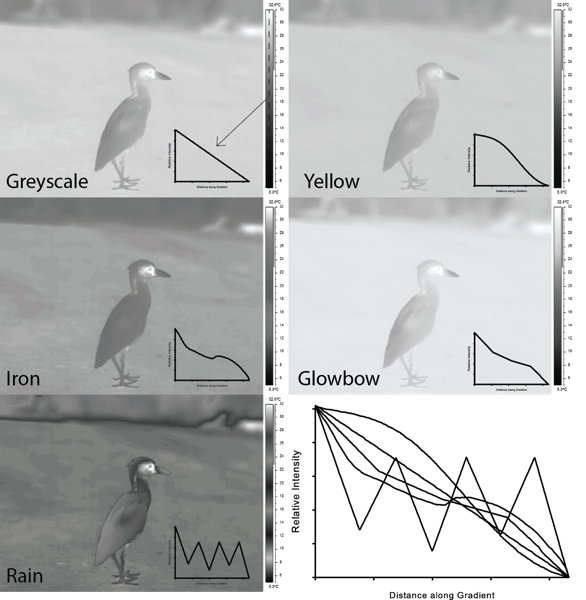

To drive home this point more clearly, I have converted every single image above to a greyscale image in Photoshop using the default greyscale convert tool:

For most of the palettes chosen (the first 4), the conversion to greyscale does not really obscure the image too much, but it still transforms the images. In other orders, darker greys clearly correspond to cooler colours, lighter greys to warmer colours. The exception is the Rain palette. When converted to greyscale it appears saturated in some places, the bird's image is nicely delineated (due to the steep contrast in intensity in places), but certain greys are repeatedly used that correspond to different temperatures. In other words, it is difficult to tell for certain what colour corresponds to what temperature.

So, the morale of the story? This may not be a problem if you have a colour printer or access to a computer screen to view your colour images, but not all journals will publish in colour, and not all people will view the work in colour (e.g. referees of your papers like myself who are given black and white versions of your manuscript and are left scratching their heads wondering what the images mean!), so I think it pays to consider the effect of palette choice on how others may interpret (or get confused by) your thermal images.

Personally, I usually use the Iron palette and it turns out to have a non-monotonic change in intensity along the gradient of temperatures, which means that there may be some error in a greyscale conversion from this particular choice. I guess I could choose a more forgiving palette, but I still like the colour option for presentations myself.

You could always opt for greyscale straight from the thermal imaging device itself, and then generate boring looking images! To each their own.

My reasons will be illuminated below, but suffice it to say it relates ultimately to contrast and detectability of different temperatures through the use of colour itself.

From a computational perspective these concerns are not important. Almost all thermal imaging devices actually provide a proper temperature estimate for each pixel on the screen and as the images are typically stored in proprietary format in 12 or 14 bit files, this is not a concern from a quantitative perspective.

However, images captured are eventually converted into a digital format that is easily visualized by others, typically a jpg, png, tiff or bmp file. When presented online, then, you have a colourised rendition of temperature that is essence a filter of the real data mapped onto a pre-existing spectrum. This spectrum of colours is referred to as a palette in most graphical software.

There are a number of palettes that you might find available on your thermal imaging camera:

From left to right, these palettes are described as: Greyscale, Iron, Rain, Glowbow and Yellow (terminology comes from FLIR™). Each palette 'translates' temperature into a specific colour, with cold colours at the bottom (typically darker colours) and warm colours at the top (typically lighter colours).

At first glance it might be tempting to choose the funkiest colours, since it looks 'pretty' (this is a common reaction I get from people when I show them thermal images). Indeed, for some purposes this is entirely appropriate. Some palettes were designed specifically to create a large contrast in colour intensity across a narrow range of temperatures.

People generally do not believe me until i demonstrate it, but I often prefer to use the greyscale palette when imaging animals in the field for the simple reason that it is easier to focus on edges. Although greyscale might not offer a large degree of contrast between similar temperatures, it is a simple, natural scale of intensity where black is the lowest intensity, white is the highest intensity and greys provide a gradient of intensities in between.

For presentation purposes and for publication purposes, however, a visually appealing colour might be appropriate (instead of greyscale). My own favourite palette is the Iron palette, as demonstrated in the following image of Yellow Crowned Night Heron from Galapagos:

Note how I have set the temperature range to go from 22 to 32C, where 22 is the lowest colour on the gradient and 32 is the highest. This maximizes the potential contrast of temperatures within the visible colour palette without saturating or eliminating any potential temperature.

So, why all the fuss about palette choice? Let's consider the same image as I've shown you above, but this time using 5 different palettes. I have purposely rescaled the image to range from 5 to 32C, which actually masks some of the potential colour differences but it also shows how the different palettes may obscure potential temperature differences.

The picture above shows the yellow crowned night heron depicted using 5 different palettes. Inset line graphs depict the "intensity" of the gradient scale used in common units. All I did was import the images into ImageJ and drew a line down the gradient to obtain the "grey intensity" as a function of the colour palette. All palettes are compared in the lower right-hand graph to show how these different palettes translate "intensity" differently.

Although the human eye can certainly detect chromatic signals (i.e. different colours), the achromatic signals are what I am trying to highlight above. See how the different palettes show varying degrees of linearity and non-linearity. Clearly the greyscale gradient shows a monotonic decline in intensity, as you would expect for an achromatic response.

The other palettes however are not all the same as the greyscale. Sadly, my own favourite palette is shows a slightly curvilinear function with some intensities rising before falling again. The palette that comes closest to a greyscale, slightly monotonic decreasing palette is FLIR's Yellow palette.

Note how weird the Rain palette looks. The intensity rises and falls along the gradient itself. What this means is that your eye may be drawn to changes in achromatic signals in the colour palette and mistakenly consider them to be an incorrect temperature change. The Rain palette is an example of one of those favoured by people who initially play with thermal cameras. The images look striking, but my pet peeve about it is that it creates unnatural contrasts in colours that do not correspond to the actual temperature gradient. It also does not help that the beak and the back feathers look 'warm' because I am accustomed to yellow colours being warmer than red colours.

To drive home this point more clearly, I have converted every single image above to a greyscale image in Photoshop using the default greyscale convert tool:

For most of the palettes chosen (the first 4), the conversion to greyscale does not really obscure the image too much, but it still transforms the images. In other orders, darker greys clearly correspond to cooler colours, lighter greys to warmer colours. The exception is the Rain palette. When converted to greyscale it appears saturated in some places, the bird's image is nicely delineated (due to the steep contrast in intensity in places), but certain greys are repeatedly used that correspond to different temperatures. In other words, it is difficult to tell for certain what colour corresponds to what temperature.

So, the morale of the story? This may not be a problem if you have a colour printer or access to a computer screen to view your colour images, but not all journals will publish in colour, and not all people will view the work in colour (e.g. referees of your papers like myself who are given black and white versions of your manuscript and are left scratching their heads wondering what the images mean!), so I think it pays to consider the effect of palette choice on how others may interpret (or get confused by) your thermal images.

Personally, I usually use the Iron palette and it turns out to have a non-monotonic change in intensity along the gradient of temperatures, which means that there may be some error in a greyscale conversion from this particular choice. I guess I could choose a more forgiving palette, but I still like the colour option for presentations myself.

You could always opt for greyscale straight from the thermal imaging device itself, and then generate boring looking images! To each their own.

Saturday 1 March 2014

Thermal Imaging Advice

It seems that about once a month, I am asked by colleagues, their students, strangers, or even my family about thermal imaging. Typically these requests come as a email for help in selecting a thermal camera, or simply in whether they could use a camera to address a question they are interested in. Given the length of time it takes to respond to every request, I am putting some advice on my blog here for future linkable reference (future edits may be employed).

I struggled myself when I started this technique but I had the advantage that I had a camera to use and experiment with. Nevertheless, yet I am still far from being an expert in optics, electronics and the physics of imaging. However, I am going to write some commonly asked questions and answers below. This is by no means an advertisement for the company mentioned below. Indeed, given how unhelpful some sales reps have been from leading thermal imaging companies, I would not want this post to be construed as an advertisement for a particular company or device. Furthermore, perhaps in 10 years we will have infrared sensing contact lenses which might make much of this blog seem out of date!

What is thermal imaging?

Ok, well, no one really asks this question, but let's start with that. Thermal imaging makes use of a camera that uses a special kind of lens that is transparent to infrared wavelengths. An image of the environment the lens captures is detected by an electronic sensor and this digital sensor converts the image into a visual digital image, typically in a pseudo colour palette. See this wiki entry for an introduction: When I refer to infrared thermal imaging, I am usually referring to a camera based technology that capitalizes on the fact that all objects that are greater than absolute zero emit some form of radiation. As a biologist, I am lucky on multiple fronts. I am usually studying objects that are warm (between -20C to 40C), which is a relatively narrow range of radiative flux and thus works well with most instruments. Given this range of temperatures, I use cameras that sense long-range infrared wavelengths (8 to 12 μm) and have a camera capable of assessing ~0.03 to 0.04C differences. Realistically, this is a very small change in temperature that might not be biologically meaningful, but if used carefully, it is helpful to have such thermal resolution in the camera to ensure that images are as 'crisp' as possible:

Another advantage to working with organisms is that most biological tissues have emissivities that are close to 1 (i.e. ~0.95-0.98). Unlike many metal objects that are 'shiny' and reflect infrared radiation, biological tissues behave in a manner that makes it easier to estimate temperature without having to be too worried about this mathematical correction. Yes, emissivity should be considered, but if you are measuring the same animal over time, the emissivity is not going to change since it is a fixed property of the object. Finally, as biologists, we're usually reasonably close to our animals so the effects of atmospheric attenuation of the infrared signal will be far less than a volcanologist who wants to stay 1 km away from an erupting volcano!

How much does a thermal imaging camera cost?

Many people ask me this same question when they seek to purchase a camera, and I rarely know what to say. We have purchased only two cameras in my lab, but I have used others in colleagues' labs around the world. I am most familiar with the FLIR SC 640 and my old Mikron 7515. Prices can range from as low as $2000 (for point and click cameras that have a very low image size of 60 pixels x 60 pixels) to as high as $50K for cameras with all the bells and whistles (640x480 pixels, great image capture capacity, software for analysis, ability to capture video etc)

Are they supposed to be so expensive?

Best to ask the sales reps. Personally, I think that sales reps are making a mint on thermal imaging cameras, and there are so many options out there where a difference of $20k doesn't seem to make much sense to me (i.e. cameras both have the same specifications in terms of physics and sensing, but one camera is more ergonomically appealing). My advise is to make sure sales reps let you try the camera out, take a picture of yourself at a distance that you might normally use the camera in the field and send it to me if you want my advice.

Can I zoom in to view objects?

Standard thermal cameras are sold with a default lens with a fixed FOV. Due to the extreme cost of building the infrared transparent lens, it is not often you will see a telephoto lens, and when you can get your hands on one, they typically provide you with an ability to change the telephoto range by 2X or 4X. This is a true optical zoom, so it definitely has an advantage in the field to have a telephoto lens, but it is difficult to find lenses that are adjustable in FOV, so once you put it in place you have to image your environment with the new lens on and cannot quickly go back and forth between the two lenses. Prices of these lenses are incredibly expensive. Usually above $4000, sometimes as high as $10000. I don't have one for my FLIR. Maybe one day I will. You can't just put any old telephoto on the camera. Normal digital camera lenses will not work since they are made with normal glass that is transparent to visible light, but absorb infrared radiation. Also, the camera software needs to know what lens is attached as it does influence the focal length and IFOV calculations which influence the estimated pixel temperature and final image.

Can I rent one?

Some companies will rent them to you. You'd have to contact sales reps. Usually rental gets pricey. With a month of renting, you'd be almost able to buy a cheap camera on your own.

Can I borrow your camera?

I have often joked that my motto is, "Have thermal camera, will travel". So far, I have done this a lot and it is fun and intellectually fulfilling. What that really means is that I won't loan it out, unless it is used by myself or my students/collaborators. Sorry.

Can I see through glass or plexiglass with the thermal camera?

No. Thermal Cameras cannot view through glass or plastics that are transparent in the visible range. In fact this presents some challenges when trying to use aquaria or image at a zoo. Just because our eyes can see an object, doesn't mean that the infrared radiation is passing through. You can, however, look into purchasing a IR transparent window of material from certain optics manufacturers. I recently purchased one from a very friendly and helpful company in China. They grew up the germanium tetrachloride crystal, polished and cut it into a 10 cm wide circular window of glass (~4mm thick) and coated it with a material that further helps ensure most IR passes through it.

How close should I be in order to detect a bird or small animal of interest?

Realistically, it is best to simply borrow a camera and try this out empirically to see what you can capture. However, you can do some quick calculations if you have certain critical information from the camera manufacturer, such as the IFOV (instantaneous field of view). With this value, you can calculate a maximum distance to target to detect a 'spot' in space of a certain size:

Distance to Target (D) X IFOV (R) = Measurement Spot Size (S) ( Source)

So, let's say you want to measure an entire songbird, which we will just approximate as a 10 cm high object. Input the 10 cm as the minimum spot size (S) and look up the IFOV for your thermal camera (mine is 0.00065 radians), and you can calculate the maximum distance to the target (D):

D = S / R = 10 cm/0.00065radians = 15384 cm or 153 metres!

Wow. That's a long way away. Unfortunately what this solves is the distance required to reach the spatial resolution ability of the thermal imager, and essentially your bird would occupy the equivalent of 1 pixel on the camera's sensor!

So, instead let's define the spot size represent an object that is 1/40th the size of the object of interest. Practically speaking, the bird would now occupy 40 pixels high which would look like a computer sprite from 1980s video games, but at least some aggregate temperature could be measured and possibly even regional parts of the body surface could be examined.

Solving D for this would lead to 3.8 metres, which means that you could be ~4 metres away from a bird and it would occupy a space on the detector of your imager 40 times higher than the minimum spot size.

Of course, the image still needs to hit the sensor and be converted into an image for storage and analysis purposes, so now the concept of digital resolution becomes important.

A 640x480 pixel thermal imaging source is an excellent resolution at present, but many of the inexpensive options for thermal imaging provide only 60x60 or 120x120 pixels for the image captured. Since the field of view is determined by the lens, a lower digital resolution captures the same image as a camera with a high resolution, but the final image created is far lower in quality.

Thus, if you think back to the bird in the field on a tree, with the 640x480 camera, it might occupy ~40 pixels high at that distance, which at least you can zoom in and analyze on a computer. Not very pretty, but minimally workable. If you had only a 60x60 resolution camera (nice and cheap), the image would be much more pixelated, since there would be approximately 10 fewer pixels per spot area.

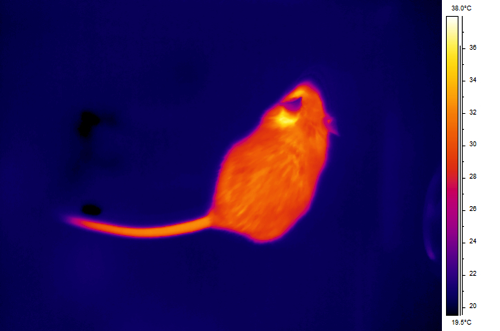

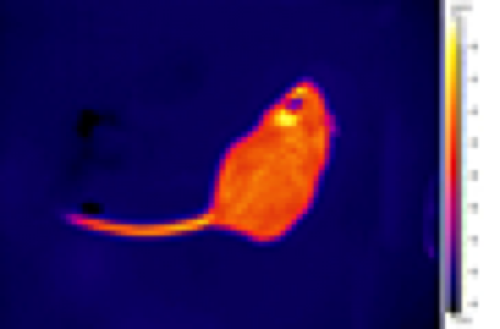

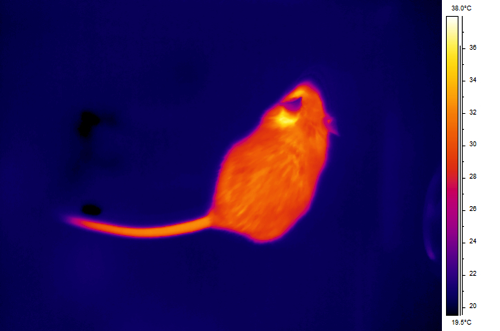

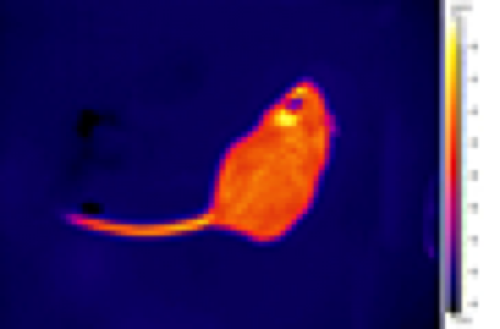

A mouse imaged with a FLIR SC660 (24o lens, distance 0.5 m, IFOV 0.65 mead)

Same image above converted to a lower resolution, but blown up to the same size for comparison. One advantage of the higher digital resolution is that you can rely occasionally on simply digital zoom to focus in on an animal in the field, since the higher overall resolution affords you the chance to do that. Realistically speaking, I prefer to be no more than 3 metres away in the field, and 1 metre away if making measurements with domestic or laboratory animals.

What problems would I encounter with using a thermal camera in the field?

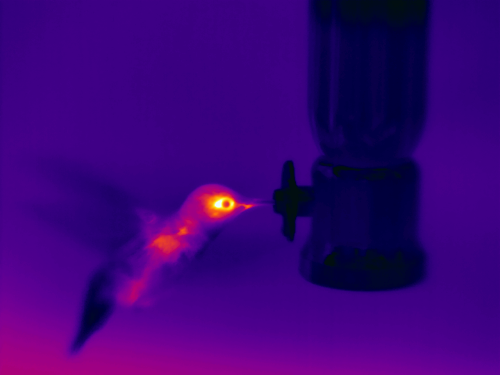

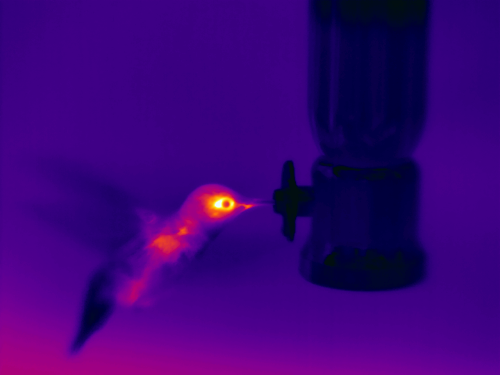

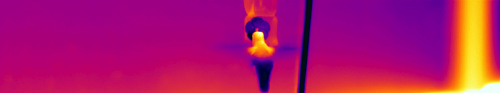

Fast moving animals are difficult to image. The minimum response time of my thermal camera is 8ms (this might be related to restrictions on the non-military use of cameras? see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Infrared_imaging#cite_note-23), which would be the equivalent of a shutter speed setting of 1/125th on an SLR camera. Anyone who has tried to capture fast moving objects knows the value of a fast shutter speed, and usually you want to have capture settings >1/500 or 1/1000. So, for example, say you wish to capture the wing beat of a hummingbird using a video frame rate of 1/30th second, here is what it would look like:

In contrast, pushing the camera to the max by capturing at 120 frames/second yields:

In both cases, you still do not obtain a sharp depiction of the wings, which appear as blurry streams as the wing beat frequency of the hummingbird is not that much slower than the frame capture rate of the thermal camera. Related to the time limits is the challenge of focussing. My thermal camera doesn't have instantaneous focus, so when objects are moving quickly within the field of view, it is difficult to keep things in focus. Sometimes you have to anticipate where the animal will be and focus on that area and simply move the camera until the bird is in focus. A poorly focussed image isn't just an inconvenience, but it can affect your temperature estimates, primarily because focusing changes the focal plane and assumptions involved in the estimate of temperature depend on knowledge of the spatial resolution of the image in focus.

What about time lapse?

Time lapse is good if you have access to a tripod and software for capturing images. The typical software that can do this will be ~$5000 from the company. The occasional camera has built in capacity to capture images at intervals, but this is usually very slow when in the field. When capturing time lapse, it is still essential to capture images in appropriate file format. It might be tempting to use the 'camera' option that allows you to capture what is really a video (NTSC, PAL). The problem with this is that any temperatures become very difficult to analyze or assess, since this video file is not digitized any longer and pixels in the video do not retain the digitized thermal information required for adequate analysis.

Why would I use a thermal camera?

To estimate heat loss and thus use the imager to estimate total metabolic expenditure in the field? - requires some time spent investigating physical equations and models to calculate heat loss. To estimate the use of certain parts of the body as thermal windows (vascular thermal radiators). - might only require you estimate the temperature of the surface of interest, along with surfaces that are not expected to change. Usually requires you have a good measurement of air temperature, wind speed, relative humidity, solar radiation. To find animal roosting sites at night - many birders ask me about this. I haven't actually tried this too much, but it should be possible, provided you have a good idea of where to start and you can get within the minimal distance required to see an individual bird. Use of information above comes with a warning: these are estimates, and 'ball park' impressions. Potential users of infrared thermal imaging should always consult with the manual for their particular imager for specific information regarding the use and utility of their camera.

What is thermal imaging?

Ok, well, no one really asks this question, but let's start with that. Thermal imaging makes use of a camera that uses a special kind of lens that is transparent to infrared wavelengths. An image of the environment the lens captures is detected by an electronic sensor and this digital sensor converts the image into a visual digital image, typically in a pseudo colour palette. See this wiki entry for an introduction: When I refer to infrared thermal imaging, I am usually referring to a camera based technology that capitalizes on the fact that all objects that are greater than absolute zero emit some form of radiation. As a biologist, I am lucky on multiple fronts. I am usually studying objects that are warm (between -20C to 40C), which is a relatively narrow range of radiative flux and thus works well with most instruments. Given this range of temperatures, I use cameras that sense long-range infrared wavelengths (8 to 12 μm) and have a camera capable of assessing ~0.03 to 0.04C differences. Realistically, this is a very small change in temperature that might not be biologically meaningful, but if used carefully, it is helpful to have such thermal resolution in the camera to ensure that images are as 'crisp' as possible:

Another advantage to working with organisms is that most biological tissues have emissivities that are close to 1 (i.e. ~0.95-0.98). Unlike many metal objects that are 'shiny' and reflect infrared radiation, biological tissues behave in a manner that makes it easier to estimate temperature without having to be too worried about this mathematical correction. Yes, emissivity should be considered, but if you are measuring the same animal over time, the emissivity is not going to change since it is a fixed property of the object. Finally, as biologists, we're usually reasonably close to our animals so the effects of atmospheric attenuation of the infrared signal will be far less than a volcanologist who wants to stay 1 km away from an erupting volcano!

How much does a thermal imaging camera cost?

Many people ask me this same question when they seek to purchase a camera, and I rarely know what to say. We have purchased only two cameras in my lab, but I have used others in colleagues' labs around the world. I am most familiar with the FLIR SC 640 and my old Mikron 7515. Prices can range from as low as $2000 (for point and click cameras that have a very low image size of 60 pixels x 60 pixels) to as high as $50K for cameras with all the bells and whistles (640x480 pixels, great image capture capacity, software for analysis, ability to capture video etc)

Are they supposed to be so expensive?

Best to ask the sales reps. Personally, I think that sales reps are making a mint on thermal imaging cameras, and there are so many options out there where a difference of $20k doesn't seem to make much sense to me (i.e. cameras both have the same specifications in terms of physics and sensing, but one camera is more ergonomically appealing). My advise is to make sure sales reps let you try the camera out, take a picture of yourself at a distance that you might normally use the camera in the field and send it to me if you want my advice.

Can I zoom in to view objects?

Standard thermal cameras are sold with a default lens with a fixed FOV. Due to the extreme cost of building the infrared transparent lens, it is not often you will see a telephoto lens, and when you can get your hands on one, they typically provide you with an ability to change the telephoto range by 2X or 4X. This is a true optical zoom, so it definitely has an advantage in the field to have a telephoto lens, but it is difficult to find lenses that are adjustable in FOV, so once you put it in place you have to image your environment with the new lens on and cannot quickly go back and forth between the two lenses. Prices of these lenses are incredibly expensive. Usually above $4000, sometimes as high as $10000. I don't have one for my FLIR. Maybe one day I will. You can't just put any old telephoto on the camera. Normal digital camera lenses will not work since they are made with normal glass that is transparent to visible light, but absorb infrared radiation. Also, the camera software needs to know what lens is attached as it does influence the focal length and IFOV calculations which influence the estimated pixel temperature and final image.

Can I rent one?

Some companies will rent them to you. You'd have to contact sales reps. Usually rental gets pricey. With a month of renting, you'd be almost able to buy a cheap camera on your own.

Can I borrow your camera?

I have often joked that my motto is, "Have thermal camera, will travel". So far, I have done this a lot and it is fun and intellectually fulfilling. What that really means is that I won't loan it out, unless it is used by myself or my students/collaborators. Sorry.

Can I see through glass or plexiglass with the thermal camera?

No. Thermal Cameras cannot view through glass or plastics that are transparent in the visible range. In fact this presents some challenges when trying to use aquaria or image at a zoo. Just because our eyes can see an object, doesn't mean that the infrared radiation is passing through. You can, however, look into purchasing a IR transparent window of material from certain optics manufacturers. I recently purchased one from a very friendly and helpful company in China. They grew up the germanium tetrachloride crystal, polished and cut it into a 10 cm wide circular window of glass (~4mm thick) and coated it with a material that further helps ensure most IR passes through it.

How close should I be in order to detect a bird or small animal of interest?

Realistically, it is best to simply borrow a camera and try this out empirically to see what you can capture. However, you can do some quick calculations if you have certain critical information from the camera manufacturer, such as the IFOV (instantaneous field of view). With this value, you can calculate a maximum distance to target to detect a 'spot' in space of a certain size:

Distance to Target (D) X IFOV (R) = Measurement Spot Size (S) ( Source)

So, let's say you want to measure an entire songbird, which we will just approximate as a 10 cm high object. Input the 10 cm as the minimum spot size (S) and look up the IFOV for your thermal camera (mine is 0.00065 radians), and you can calculate the maximum distance to the target (D):

D = S / R = 10 cm/0.00065radians = 15384 cm or 153 metres!

Wow. That's a long way away. Unfortunately what this solves is the distance required to reach the spatial resolution ability of the thermal imager, and essentially your bird would occupy the equivalent of 1 pixel on the camera's sensor!

So, instead let's define the spot size represent an object that is 1/40th the size of the object of interest. Practically speaking, the bird would now occupy 40 pixels high which would look like a computer sprite from 1980s video games, but at least some aggregate temperature could be measured and possibly even regional parts of the body surface could be examined.

Solving D for this would lead to 3.8 metres, which means that you could be ~4 metres away from a bird and it would occupy a space on the detector of your imager 40 times higher than the minimum spot size.

Of course, the image still needs to hit the sensor and be converted into an image for storage and analysis purposes, so now the concept of digital resolution becomes important.

A 640x480 pixel thermal imaging source is an excellent resolution at present, but many of the inexpensive options for thermal imaging provide only 60x60 or 120x120 pixels for the image captured. Since the field of view is determined by the lens, a lower digital resolution captures the same image as a camera with a high resolution, but the final image created is far lower in quality.

Thus, if you think back to the bird in the field on a tree, with the 640x480 camera, it might occupy ~40 pixels high at that distance, which at least you can zoom in and analyze on a computer. Not very pretty, but minimally workable. If you had only a 60x60 resolution camera (nice and cheap), the image would be much more pixelated, since there would be approximately 10 fewer pixels per spot area.

A mouse imaged with a FLIR SC660 (24o lens, distance 0.5 m, IFOV 0.65 mead)

Same image above converted to a lower resolution, but blown up to the same size for comparison. One advantage of the higher digital resolution is that you can rely occasionally on simply digital zoom to focus in on an animal in the field, since the higher overall resolution affords you the chance to do that. Realistically speaking, I prefer to be no more than 3 metres away in the field, and 1 metre away if making measurements with domestic or laboratory animals.

What problems would I encounter with using a thermal camera in the field?

Fast moving animals are difficult to image. The minimum response time of my thermal camera is 8ms (this might be related to restrictions on the non-military use of cameras? see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Infrared_imaging#cite_note-23), which would be the equivalent of a shutter speed setting of 1/125th on an SLR camera. Anyone who has tried to capture fast moving objects knows the value of a fast shutter speed, and usually you want to have capture settings >1/500 or 1/1000. So, for example, say you wish to capture the wing beat of a hummingbird using a video frame rate of 1/30th second, here is what it would look like:

In contrast, pushing the camera to the max by capturing at 120 frames/second yields:

In both cases, you still do not obtain a sharp depiction of the wings, which appear as blurry streams as the wing beat frequency of the hummingbird is not that much slower than the frame capture rate of the thermal camera. Related to the time limits is the challenge of focussing. My thermal camera doesn't have instantaneous focus, so when objects are moving quickly within the field of view, it is difficult to keep things in focus. Sometimes you have to anticipate where the animal will be and focus on that area and simply move the camera until the bird is in focus. A poorly focussed image isn't just an inconvenience, but it can affect your temperature estimates, primarily because focusing changes the focal plane and assumptions involved in the estimate of temperature depend on knowledge of the spatial resolution of the image in focus.

What about time lapse?

Time lapse is good if you have access to a tripod and software for capturing images. The typical software that can do this will be ~$5000 from the company. The occasional camera has built in capacity to capture images at intervals, but this is usually very slow when in the field. When capturing time lapse, it is still essential to capture images in appropriate file format. It might be tempting to use the 'camera' option that allows you to capture what is really a video (NTSC, PAL). The problem with this is that any temperatures become very difficult to analyze or assess, since this video file is not digitized any longer and pixels in the video do not retain the digitized thermal information required for adequate analysis.

Why would I use a thermal camera?

To estimate heat loss and thus use the imager to estimate total metabolic expenditure in the field? - requires some time spent investigating physical equations and models to calculate heat loss. To estimate the use of certain parts of the body as thermal windows (vascular thermal radiators). - might only require you estimate the temperature of the surface of interest, along with surfaces that are not expected to change. Usually requires you have a good measurement of air temperature, wind speed, relative humidity, solar radiation. To find animal roosting sites at night - many birders ask me about this. I haven't actually tried this too much, but it should be possible, provided you have a good idea of where to start and you can get within the minimal distance required to see an individual bird. Use of information above comes with a warning: these are estimates, and 'ball park' impressions. Potential users of infrared thermal imaging should always consult with the manual for their particular imager for specific information regarding the use and utility of their camera.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)